The Book of Five Rings (Go Rin no Sho) is a classic text on strategy, combat, and philosophy, written by the legendary Japanese swordsman Musashi Miyamoto in 1644. It offers timeless wisdom not only on martial arts but also on broader topics of strategy, applicable to various fields such as leadership and business. Drawing from his own experiences as an undefeated samurai, Musashi divides his teachings into five sections, each named after one of the classical elements: Earth (Ground), Water, Fire, Wind, and Void. These books collectively guide the reader through mastering the “Way of Strategy.”

Plot Summary

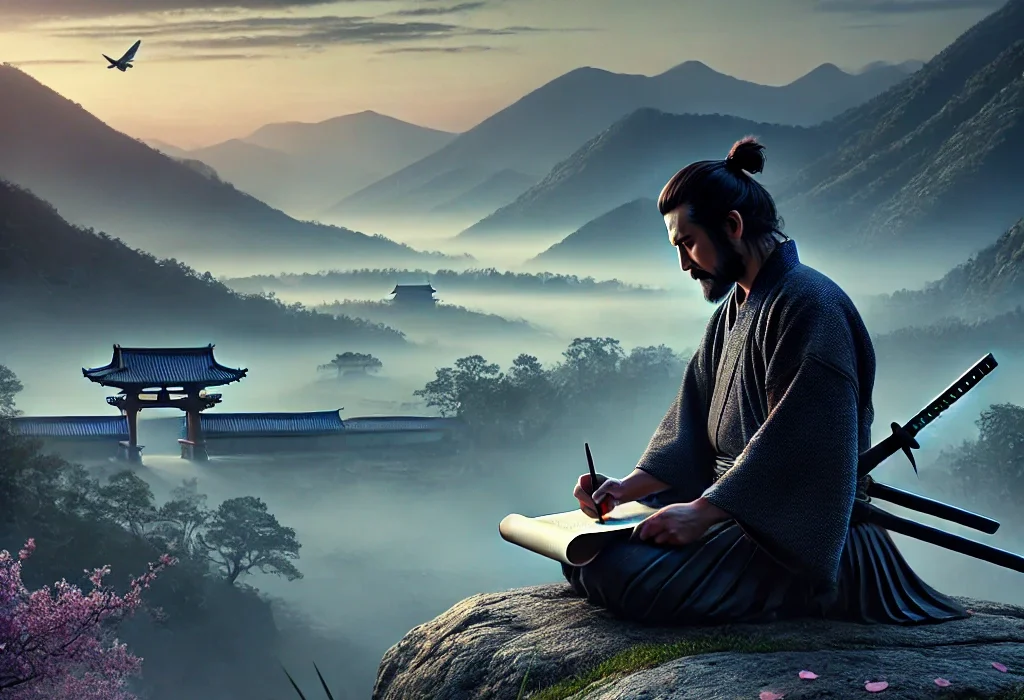

At sixty years of age, Musashi Miyamoto, the undefeated swordsman who had fought and won in countless duels, retreated to a quiet mountain in Japan. It was here, amidst the stillness, that he sought to distill a lifetime of combat wisdom into five elemental books. These books were not written for casual understanding; they were a path, a way of life, meant to be mastered through relentless discipline, not merely read. Each book unfolded like a guide to surviving and thriving in the battlefield of life, where swordsmanship was only one facet of strategy.

The first of these was the Ground Book. Musashi began by setting the foundation, just as one would for a house. A warrior’s mind, body, and spirit must be grounded in the Way of Strategy. He reflected on his early duels, those that had shaped him from a young boy of thirteen into the undefeated master he became. He had fought warriors of every school, never faltering, yet only at thirty did he realize that victory was not about skill alone. The Way of Strategy, as he came to understand it, was about perception and awareness—understanding not just your own movements but those of your enemy. A warrior must be firmly planted like the earth itself, unshakable, prepared to face any opponent, yet flexible enough to adapt to every situation. Strategy was not merely about winning a fight but mastering the principles that governed combat, life, and death.

With the Water Book, Musashi guided the reader into the fluidity of action. Water, as he described it, was shapeless but powerful, taking the form of its surroundings. This was the essence of adaptability in combat. A warrior must be like water, flowing freely between offensive and defensive stances, shifting with the movements of the enemy, always ready to strike. As water can crash or creep, so too must a warrior know when to unleash force and when to move subtly. He spoke of the long sword, the main tool of a warrior, and how its movements must become instinctual. The sword should not be seen as separate from the warrior but as an extension of his will. In combat, the warrior must move as naturally as water, with seamless transitions, understanding the rhythm and timing of each battle. To know the rhythm of any situation was to control it.

Next, Musashi led the reader through the fierce pages of the Fire Book. Fire was the element of battle itself—relentless, consuming, driven by instinct and intensity. Musashi believed that when a warrior engaged in combat, there could be no hesitation. The spirit of fire must drive each action, whether it was a one-on-one duel or a battle with thousands. In this book, Musashi detailed the principles of attacking with speed and decisiveness. He revealed that battles, both great and small, were won by mastering the timing of not just one movement but the entire flow of combat. In the chaos of the battlefield, a warrior must remain focused, able to make quick, accurate decisions that lead to victory. The fire burned fiercely, and so must the warrior’s spirit in the heat of conflict.

But as a warrior must understand fire, he must also comprehend the winds of change. In the Wind Book, Musashi turned his attention to the strategies of other schools. Wind was tradition, the ideas that had shaped warriors before him, the methods that many still followed. Yet Musashi, ever the unconventional strategist, sought to show the flaws in these old ways. He saw that many schools focused too much on form, teaching techniques that were rigid and decorative, more concerned with appearances than effectiveness. Musashi warned against becoming too attached to specific methods or styles. The true Way of Strategy, he taught, was to adapt, to take what worked and discard what did not. A warrior should study the old ways but must not be bound by them. Tradition could guide, but it should never limit one’s growth. The wind, like strategy, was ever-changing, and a warrior must be ready to shift with it.

Finally, Musashi presented the Void Book. In this, the most abstract and philosophical of his teachings, Musashi explored the concept of emptiness—of nothingness. The Void represented the unknown, the formless, the space between thoughts and actions. It was not something that could be easily understood through words; it was a state of being that had to be experienced. Musashi believed that the highest level of mastery came when a warrior could fight without conscious thought, moving naturally, instinctively, in perfect harmony with the world around him. This was the essence of the Void—the ultimate state of awareness where the warrior and the world were one. In this state, a warrior no longer needed to think about his movements; he simply acted. Victory came naturally, effortlessly, as if it had already been decided by the universe.

Each of the five books was more than a lesson in swordsmanship—they were teachings on life itself. Musashi’s Way of Strategy was not confined to the battlefield. It was a path to self-mastery, to understanding the rhythms of the world and one’s place within it. The principles he laid out could be applied to any challenge, any struggle. Victory, Musashi taught, was not just about defeating others but about mastering oneself. It was about seeing the truth of a situation clearly, moving in harmony with it, and acting decisively when the time was right.

As Musashi concluded his teachings, the reader could sense the weight of the journey that lay ahead. The Way of Strategy, as Musashi had lived and written it, was not a simple path. It required dedication, practice, and an unrelenting spirit. But for those who walked it, the rewards were great. The warrior who truly understood the Way of Strategy would not only be victorious in battle but would find harmony in all aspects of life. The Way was not just about winning—it was about becoming invincible in mind, body, and spirit.

Main Characters

Musashi Miyamoto: The author and central figure of the book, Musashi is not only a legendary swordsman but also a philosopher and strategist. Throughout the text, he shares insights from his extensive combat experience, reflecting on the deeper meaning of strategy, beyond just technique and weaponry. His evolution from a youthful fighter to a mature strategist frames the book’s lessons.

The Opponent (Abstract): Although not a character in the traditional sense, the concept of the opponent is ever-present. Musashi consistently references “the enemy” in his teachings, urging the reader to understand their movements, intentions, and spirit as an integral part of mastering strategy.

Theme

The Way of Strategy: At the heart of Musashi’s teachings is the Way of Strategy (Heiho), a philosophy that goes beyond sword fighting. He stresses the importance of adaptability, awareness, and discipline. Strategy is not merely about overpowering an opponent but involves understanding timing, positioning, and the principles that govern combat and life.

Mastery Through Discipline and Practice: Musashi advocates relentless training as the path to mastery. He insists that without practice, the Way cannot be truly understood. This dedication to continuous improvement is a recurring theme, applicable to any pursuit.

Harmony Between Spirit and Body: Musashi frequently emphasizes that the spirit and body must be aligned. In combat and in life, the warrior must maintain a calm yet determined spirit, never letting emotion or tension disturb their flow. This harmony is essential to achieving victory.

The Fluidity of Water: The concept of fluidity, most prominently discussed in the Water Book, serves as a metaphor for adaptability in strategy. Like water, one must adjust to the form and situation, moving effortlessly between different techniques and approaches.

Writing Style and Tone

Musashi’s writing is concise, direct, and methodical, reflecting the disciplined mindset of a warrior. His tone throughout the text is authoritative, born from the wisdom of lived experience. He often addresses the reader with the clarity of a teacher instructing a student, encouraging a deep and personal engagement with the material. There is a sense of urgency in his words, pushing the reader to internalize his lessons through rigorous practice and contemplation.

Despite the formal and instructional nature of the text, Musashi often employs vivid metaphors drawn from nature and daily life—such as comparing strategy to carpentry or the movement of water. These comparisons make complex ideas more accessible and illustrate his belief in the interconnectedness of all things. The tone, while instructional, is also philosophical, often prompting reflection on the greater purpose behind the techniques being discussed.

We hope this summary has sparked your interest and would appreciate you following Celsius 233 on social media:

There’s a treasure trove of other fascinating book summaries waiting for you. Check out our collection of stories that inspire, thrill, and provoke thought, just like this one by checking out the Book Shelf or the Library

Remember, while our summaries capture the essence, they can never replace the full experience of reading the book. If this summary intrigued you, consider diving into the complete story – buy the book and immerse yourself in the author’s original work.

If you want to request a book summary, click here.

When Saurabh is not working/watching football/reading books/traveling, you can reach him via Twitter/X, LinkedIn, or Threads

Restart reading!