The Art of War was written by Niccolò Machiavelli and published in 1521. Unlike his better-known political treatise The Prince, this book is a dialogue about military strategy and organization, framed within a conversation between Fabrizio Colonna, an experienced and respected military commander, and several Florentine citizens. The dialogue takes place in the gardens of Cosimo Rucellai, a friend of Machiavelli, and is set against the backdrop of Renaissance Italy, a period rife with political instability and military conflict. Machiavelli argues for a return to classical Roman military practices, offering insights on the role of discipline, civic duty, and military organization in sustaining a strong state.

Plot Summary

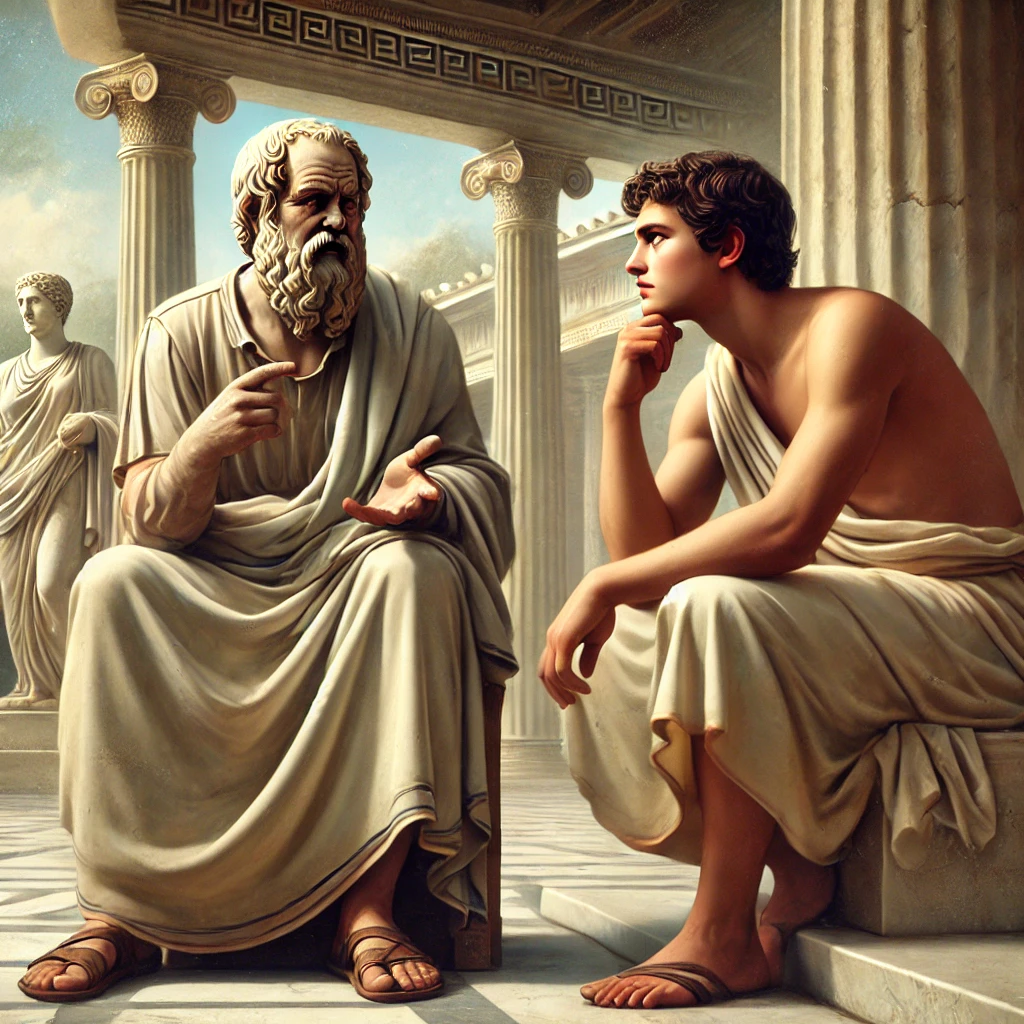

Under the shaded canopy of Cosimo Rucellai’s garden, a group of noblemen gathered one hot afternoon, eager to engage in a conversation with Fabrizio Colonna, a renowned military commander. Cosimo, their host, was curious. The air was heavy with thoughts of Italy’s political unrest, the frequent wars, and the shifting loyalties of mercenaries. It was a time when foreign soldiers, hired at the whim of wealthy rulers, determined the fates of cities. But Fabrizio spoke of a different world—one grounded in ancient virtue and discipline.

As they settled into their seats, Fabrizio began to share his thoughts. “War and peace are not so different,” he declared. “A city’s strength lies not in its wealth or walls, but in the hearts of its people.” He spoke of the ancient Roman legions, an army of citizens, each man bound by loyalty to his homeland. In Rome, war was not a profession but a duty. The men who fought were farmers, craftsmen, and merchants—people who had a stake in the land they defended.

The young men listening were intrigued. They had grown up in a world where soldiers were paid to fight. These mercenaries, though skilled, cared little for the cities they protected. When war ended, they turned to looting or worse, raising new armies to terrorize the land. Why had things changed? Fabrizio’s eyes gleamed as he spoke of the corruption of contemporary armies. “A soldier who fights for gold has no reason to protect a city unless the gold keeps flowing. But a man who fights for his home—he is bound by love, by honor, by necessity.”

Cosimo, keen to understand, leaned forward. “But can such an army be created again? How do you find such men?” Fabrizio smiled, knowing this was the heart of the matter. “It begins with discipline, with training, and with leadership. An army must be built from its people. When the Romans conscripted soldiers, they selected from every part of society, not just the poor or the desperate, but men of virtue and ability. These men were trained rigorously, taught not just to fight but to think, to act as one unit. Each man knew his role in the larger whole.”

The young men were captivated by this vision of an ideal army. It was unlike anything they had seen in Italy, where mercenaries came and went with the tide of money. Fabrizio, however, was insistent. “Mercenaries will ruin us,” he warned. “They have no loyalty. Look at how Italy has been torn apart—betrayed not by foreign invaders, but by our reliance on these sell-swords.”

His words struck a chord. They had all seen it. The cities of Italy, from Florence to Venice, had been played against each other by mercenaries, armies bought and sold by the highest bidder. Victory belonged not to the bravest, but to the richest. But Fabrizio offered a different future, one that harked back to a time when men fought for something greater than coin.

“The strength of a republic,” he said, “comes from its citizens. If the people are trained to defend their city, they will not only be soldiers—they will be guardians of peace. A soldier should not be a man apart from the rest of society. He must be a part of it, living in peace, but prepared for war.”

The garden seemed to grow quieter as Fabrizio’s voice lowered. He spoke now of the civic virtue that bound a republic together. In Rome, the soldiers were farmers by day, warriors when called. Their training was continuous, their loyalty unshakable. “But,” Fabrizio cautioned, “this is not something that can happen overnight. It requires the will of the people and the wisdom of their leaders. It requires laws, discipline, and a shared sense of purpose.”

The men around him pondered this. Could such an army be raised in their own cities? Would the people of Florence or Venice take up arms not for pay but for duty? Fabrizio believed it was possible. He spoke of the importance of teaching young men the skills of war from an early age, not so they would grow to be professional soldiers, but so they would be ready to defend their homes if the need arose.

Cosimo was curious about the specifics. How should such an army be armed? Fabrizio described the weapons the Romans used—the shields, the swords, the careful balance of light and heavy infantry. “But it’s not just the weapons,” he said. “It’s the discipline. Soldiers must be trained to fight as one, to move as a unit. Every man must trust the man beside him.”

The conversation turned to tactics. Fabrizio detailed how the Romans would arrange their troops in battle, how they would advance in coordinated movements, overwhelming their enemies not with brute strength but with precision. He contrasted this with the chaotic methods of the mercenaries, whose only loyalty was to their commanders, and whose only goal was survival. “A mercenary thinks of his own skin. A citizen thinks of his city.”

As the day wore on, Fabrizio returned to the heart of his argument: the connection between a strong military and a strong state. A republic that could not defend itself would soon fall. But more than that, an army of citizens, trained and disciplined, would ensure not only the survival of the state but its prosperity. “The greatest cities of the ancient world,” he said, “did not rise through conquest alone. They rose because their people were united. War, like politics, is a matter of unity and virtue.”

By the time the sun began to set, the men in Cosimo’s garden had been given much to think about. Fabrizio’s words echoed in their minds—the call for a return to discipline, to civic virtue, and to the ideals of ancient Rome. They had come seeking knowledge about the art of war, but what they found was something deeper: a vision of a society where citizens were not just soldiers but protectors of peace, bound by a shared duty to their city and to each other.

The conversation ended as it had begun, with quiet contemplation. But Fabrizio had planted a seed in their minds, a seed that might one day grow into something far greater than any one of them could imagine.

Main Characters

Fabrizio Colonna: A military expert and the central figure of the dialogue, Fabrizio represents Machiavelli’s views on warfare. His character is based on a real historical figure who was a prominent military commander. Throughout the dialogue, Fabrizio discusses various military strategies, the importance of discipline, and the revival of ancient Roman military customs.

Cosimo Rucellai: The host of the discussion, Cosimo is a nobleman and a central figure in Florence’s intellectual circle. Although he doesn’t dominate the conversation, his presence helps to anchor the dialogue and he poses thoughtful questions that allow Fabrizio to expand on his views.

Zanobi Buondelmonti, Battista Della Palla, and Luigi Alamanni: These young men are part of the conversation and serve as Fabrizio’s interlocutors. They represent different facets of Florentine society and provide contrasting perspectives that fuel the discussion on military theory, though their contributions are more limited compared to Fabrizio’s.

Theme

The Role of Discipline in Military Success: Machiavelli, through Fabrizio, repeatedly emphasizes the importance of strict discipline and training. He argues that the effectiveness of an army lies not in numbers but in the quality of its soldiers, which can only be ensured through rigorous training and proper organization.

Civic Duty and Republican Virtue: A major theme is the connection between military service and citizenship. Drawing from Roman practices, Machiavelli advocates for a citizen-soldier model where citizens defend their own state rather than relying on mercenaries. This intertwines with the idea that a healthy republic requires active participation from its citizens, especially in defense.

Reviving Ancient Military Practices: Machiavelli romanticizes the Roman military system and stresses the need for Renaissance Italy to adopt similar tactics. He criticizes contemporary reliance on mercenaries and advocates for the establishment of national armies based on Roman principles, which he believes are more virtuous and effective.

War as an Extension of Politics: Like The Prince, The Art of War reflects Machiavelli’s belief that war is a necessary tool of statecraft. A well-prepared army is essential not just for defense, but also for maintaining and expanding a state’s power. This pragmatic view ties military organization directly to political stability and success.

Writing Style and Tone

Machiavelli employs a formal and didactic tone throughout the dialogue. His language is structured and systematic, reflecting his intention to instruct rather than merely entertain. Fabrizio Colonna, the character through whom Machiavelli speaks, is articulate and methodical in presenting his ideas, often using historical examples, especially from Roman history, to justify his arguments.

The style is conversational but dense, with long, elaborate explanations of military strategies. The dialogue format allows Machiavelli to explore different viewpoints while still steering the reader toward his conclusions. The tone reflects Machiavelli’s realist approach to politics and warfare, focused on practicality and the harsh realities of power, much like The Prince. Despite being a military treatise, the text is deeply philosophical, questioning the relationship between warfare, civic responsibility, and morality.

We hope this summary has sparked your interest and would appreciate you following Celsius 233 on social media:

There’s a treasure trove of other fascinating book summaries waiting for you. Check out our collection of stories that inspire, thrill, and provoke thought, just like this one by checking out the Book Shelf or the Library

Remember, while our summaries capture the essence, they can never replace the full experience of reading the book. If this summary intrigued you, consider diving into the complete story – buy the book and immerse yourself in the author’s original work.

If you want to request a book summary, click here.

When Saurabh is not working/watching football/reading books/traveling, you can reach him via Twitter/X, LinkedIn, or Threads

Restart reading!